A number of things recently have caused me to think about how common land, as a particular species of the commons, relate to ideas of interiority. Especially when the term most associated, negatively, with the commons is ‘enclosure’.

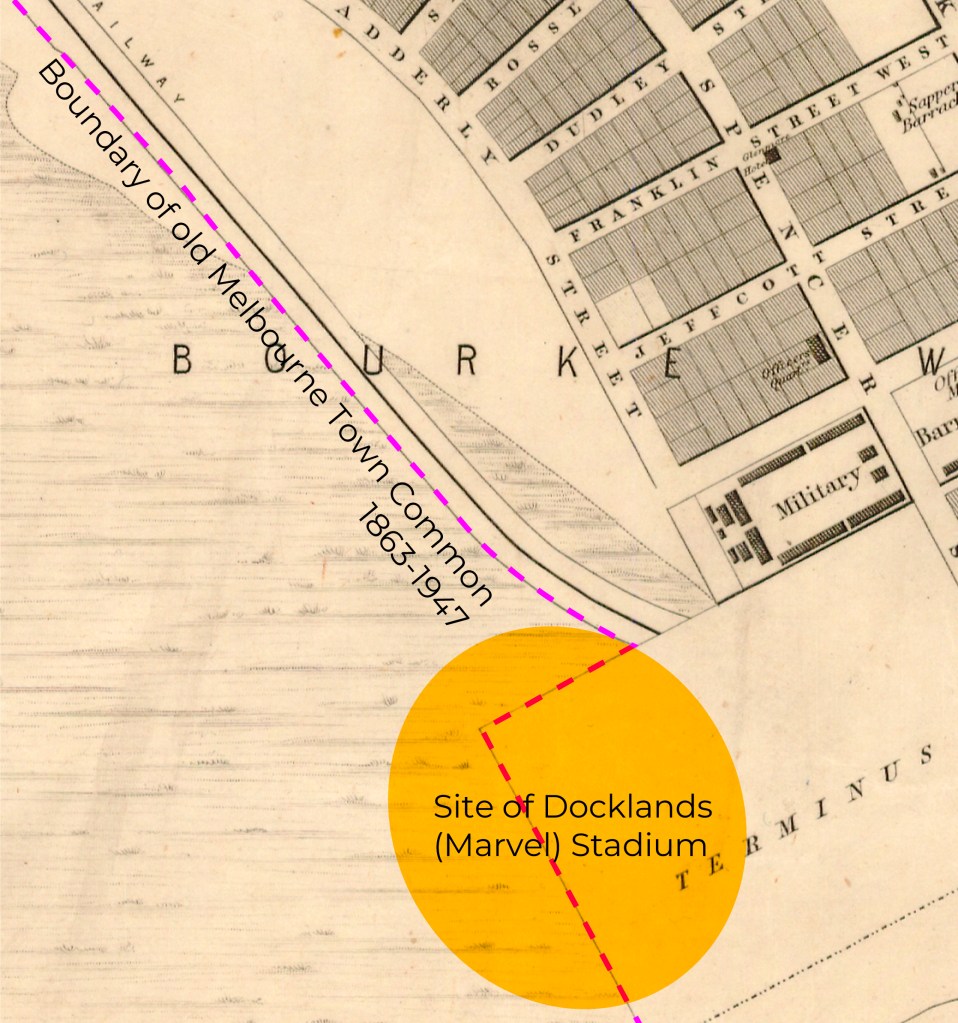

Scale is a concept often used to describe the difference between the interior and the city or the landscape. I am not so convinced: In An Archaeology of the Affective Commons: Summoning the Border in Motion, in UOU Special Issue In Detail, I explored the boundaries of the huge ex-commons of Melbourne at the micro-scale. Instead, the common, interior or exterior, demands that attention be paid to how space is lived, negotiated, improvised, and temporally inhabited – even when legally erased.

This image taken through Marvel Stadium – at once interior, building, landscape and city fragment – summons the old, intangible, border of Melbourne Town Common as it passes through it in the way shown on the map.

Base Map: Melbourne and its suburbs [cartographic material] / compiled by James Kearney, draughtsman ; engraved by David Tulloch and James D. Brown. Victoria. Surveyor-General.[Melbourne] : Andrew Clarke, Surveyor General 1855. Overlay: Alessandro Zambelli.

Almost following Mark Pimlott, the stadium is sometimes a “public interior” [1] and in this context is understood not as a building type per se, or a legally defined public space, but as an interior condition of shared occupation, ambiguously contiguous with the city and operating as a residual or dormant common awaiting re-summoning.

[1] Mark Pimlott, The public interior as idea and project (Jap Sam Books, 2016).