These are some fragments of something coming out soon in UOU scientific journal #10

An Archaeology of the Commons stages an encounter between two systems: the commons – as place and practice – and archaeology understood as materially grounded storytelling. Following Lauren Berlant’s invitation to attend to detail, both may be treated as affective infrastructures that become legible through instruments of urban governance: title plans, parcels, cadastral surveys, easements, and public works. The commons are most intensely performed at their boundary where unlike a border, they become dynamic, constitutive processes through which social, ecological and political relations are continually remade.

Working with Melbourne’s vestigial town common, I describe a re-enactment of “beating the bounds” – a reactivation of a dormant colonial edge – not as a revenant to be feared but as material to be reworked. Here archaeology-as-commoning is developed as a performative method – walking, drawing, filming and incantation – in order to reanimate erased sites and redistribute their narratives into shared cultural life. Attention to micro-details – fence lines, survey coordinates, species names, culverts and benchmark stones – guides a practice that both records and makes space.

Here as well, methodologically, cartography, technical drawing, field inscription and film are gathered into critical dialogue. Maps are read as cultural instruments that stabilise abstraction while insisting on generative frictions between representation and lived ground. Through slow, materially attentive inscription and speech, the work exposes how colonial spatial logics persist in urban seams – offset grids, easements, utility corridors, “paper roads” – and how they can be unsettled. The contribution is threefold: a reframing of commons boundaries as infrastructures of relation; a method for their excavation through performative, multi-scalar practices; and a demonstration that detailed attention can open new imaginaries for urban common land.

Figure 1. ‘Girls Beating the Bounds’ at a fence near St Albans in Hertfordshire, 1913, (Soth 2020).

“[Un]Beating the Bounds

In May 2025 Eleanor Suess, Hélène Frichot and I beat the bounds of two of the four ‘lost’ fragments of old Melbourne Town Common in a contemporary re-enactment of ancient English communal practices.[1] These practices, medieval in origin, inscribe memory into bodies through shared, performative action, marking and reaffirming parish boundaries (then – see Figure 1) and lost commons (now); across kerb edges, fence lines and bridge abutments, but also where no border trace remains; through buildings and across football fields.”

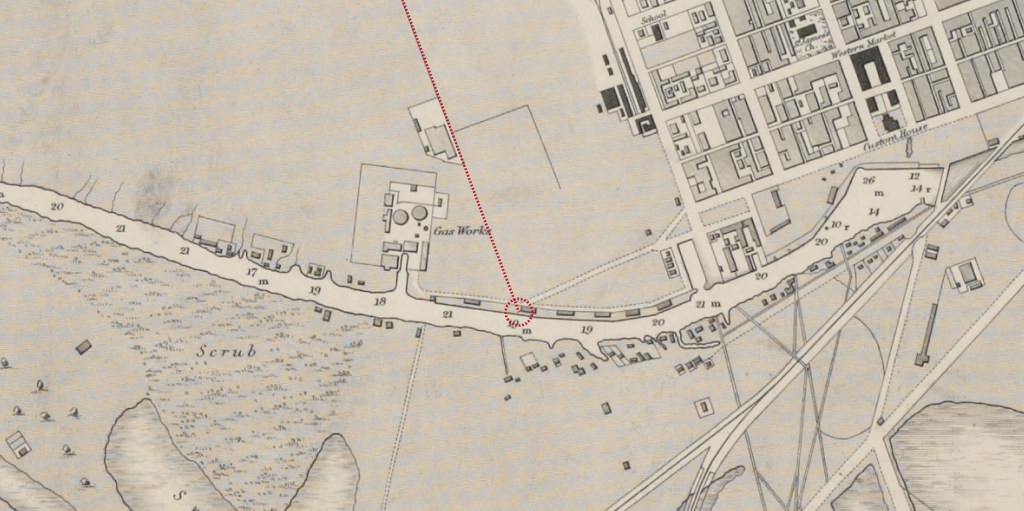

Figure 2. Beating the Bounds of Melbourne Town Common first filming location indicated in dashed red line. Using: Victoria, Australia, Port Phillip. Hobson Bay and River Yarra leading to Melbourne (1864). Creator deceased 1872, out of copyright. Source: National Library of Australia, Trove.

Figure 3. Detail of map used to plan filming route. Locations derived from text description and map in Figure 2.

“Borders, Boundaries and Edges

I had established the likely, approximate, border of the old common fragment by re-mapping the textual description of it (Barkly 1863 [published 1915]) via a contemporaneous map (Figure 2) onto a modern digital one (Figure 3). With our phones we followed on foot this messy re-representation of a 162 year old, text-only, land law proclamation.”

Figure 4. Cleaning (at) the boundary of old Melbourne Town Common. Film still from: Beating the Bounds of Melbourne Town Common. Eleanor Suess, 2025.

“In Figure 4 the congruence of line and border allows one to, bathetically, see the window cleaners literally cleaning the edge, projected upwards, of the common.”

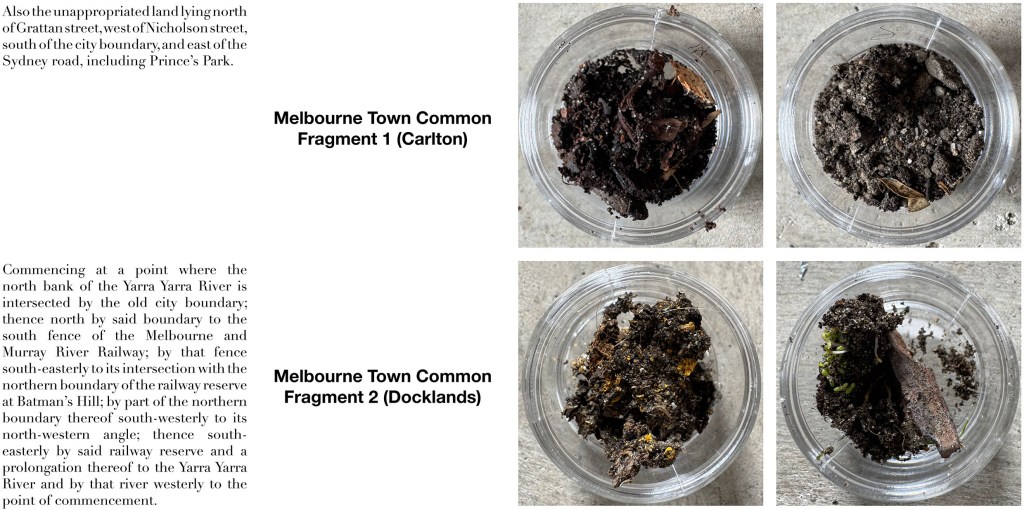

Figure 5. Text describing the boundary of Melbourne Town Common (Barkly 1863 [published 1915]). Soil collected at the boundary of old Melbourne Town Common (Suess and Zambelli 2025) – location as Figure 2., Alessandro Zambelli, 2025.

“If borders and cartography are abstractions that both obscure lived experience and offer a messy alternative, then drawing and archaeological inscription, I would argue, also offer a way back into the material and the gestural, just as soil collected at the boundary (Figure 5) reminds us that, yes, we can ‘pick up’ the border.”

[1] This re-enactment was first exhibited as: (Suess and Zambelli 2025) (Suess and Zambelli 2025) Then published as: (Zambelli and Suess 2025 [in press])

This work, in turn, builds upon related work done by Siobhan O’Neill as part of our ‘Wastes and Strays’ project: (O’Neill 2021) and (Rodgers et al. 2024)